What is PDCA?

So you’ve got a problem on your hands: It’s thorny, complex and layered. Consider PDCA. Similar to the Japanese concept of Kaizen, it’s a simple, iterative management approach for testing change and eliminating pain points. PDCA stands for ‘Plan, Do, Check, Act’. Its goal? Continuous improvement within organisations over time.

Where did PDCA come from?

PDCA originated in 20th-century manufacturing practices, but thanks to its simplicity and success at solving problems, the practice is now employed by many industries.

The American engineer and professor W. Edwards Deming named the ‘Shewhart Cycle’ for his mentor Walter Shewhart, a statistician often called ‘the father of modern quality control’. (Deming was perhaps most famous in Japan, where his ideas helped influence the nation’s post-war industrial recovery.)

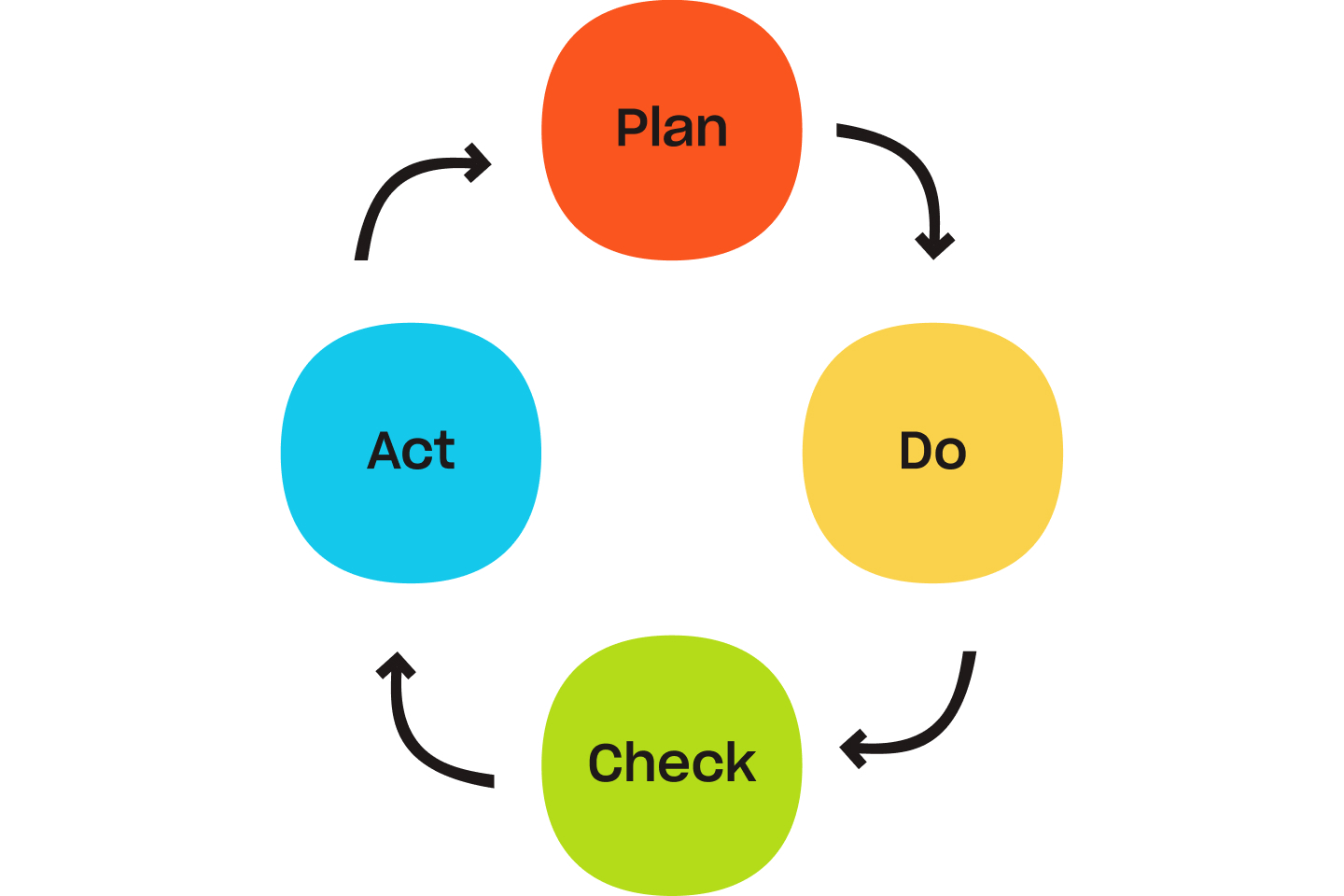

Students of Deming’s lectures coined the name PDCA – ‘Plan; Do; Check; Act’. As you’ll see from the image shown here, Deming actually preferred ‘Study’ to ‘Check’, calling it the Plan-Do-Study-Act, or ‘PDSA cycle’.

‘Study’, thought Deming, placed more emphasis on analysing results rather than simply checking what had changed. (You’re going to collect a lot of data in this process; may we recommend Dropbox cloud storage?)

In America today, we largely know the approach as PDCA, the PDCA cycle or the Deming cycle. Its design and logic overlapped with other contemporaneous manufacturing-based quality management approaches, such as Lean Manufacturing, Kaizen and Six Sigma.

How does the PDCA cycle work?

A PDCA cycle involves 4 steps: Plan, Do, Check, Act. Conduct the process in a linear fashion, so the completion of one cycle ties into the beginning of the next. Here’s what we mean:

Plan

Understand your organisation’s current state and the desired state. The purpose of the planning phase is to define your goals, decide how to accomplish them and consider how you’ll measure your progress. Different organisations will approach PDCA uniquely. Some may split it into several intermediary steps (such as by using the DMAIC process).

If you want to leverage a time-sensitive opportunity, your planning should focus on the processes or actions necessary to target that opportunity. If you’re looking to solve a process problem, you may need a root cause analysis before you can move forward with a plan. (Here’s how to do a root cause analysis to help identify and action problems.) Use data – whether pre-existing process data or analysis from previous PDCA cycles – to help formulate your approach.

Do

Once you have your plan of action or a potential solution, test it. The Do step is when you test your initial proposed changes. However, this should be an experiment, and not the point at which you are fully implementing a solution or process change. Conduct this phase at a small scale in a controlled setting. Protect it from external factors and don’t let it disrupt other processes or day-to-day operations. The point of this phase is to collect data and information, as this will inform the next PDCA stages.

Check

After completing the pilot test, examine whether your proposed changes and solutions had the desired effect. The Check phase is when you analyse the data gathered from the Do phase and compare it to your original goals. Evaluate your testing approach, and check whether changes to the method you established in the Plan phase may have affected the process. Evaluate how successful you’ve been, and decide what to take into the next step of the process. In fact, you may choose to run another test, repeating the Do and Check phases until you find a satisfactory solution to take to the Act phase.

Act

Upon reaching the end of the cycle, you and your team should have identified a proposed change from the process to implement. However, PDCA is called a ‘cycle’ for a reason, because whatever changes you implement in the Act phase aren’t the end of your process: Your new-and-improved product, process or solution should form the new baseline for further iterations of the PDCA cycle.

Why should you use PDCA?

PDCA is a standardised approach and philosophy for team members and employees to use to resolve issues and continuously improve their work.

‘OK’, you might be thinking, ‘but this could be said of many management and quality control techniques. What makes PDCA special compared to the others?’

Here at Dropbox – where we employ PDCA on the regular to test amazing new products – we think it’s because the four steps are simple, intuitive and easy to implement. It’s a cinch to bake them into your organisational culture and processes.

Because it’s iterative, PDCA also helps you iron out mistakes and identify root causes, preventing them from occurring down the line. As you continue to test different solutions, you’ll collect data and experience in understanding the process. (Ahem, may we recommend DocSend’s analytics prowess?)

At this point, PDCA becomes more than a problem-solving approach: It can give you information to strengthen your entire organisation.

Its fans also love how adaptable PDCA is; what needs to be defined or planned is ultimately up to you and your team, as long as it can sustain the four simple steps. This adaptability makes PDCA scalable, as it can be sized to any situation and any team – even a team of one.

When should you use (or not use) PDCA?

Some problem-solving and management approaches can be time- and resource-intensive to apply – not to mention hiring consultants – but PDCA’s flexibility lends itself to solving many issues on the cheap.

If you are looking to make consistent improvement to work processes, PDCA is a good bet. If you’re someone who needs to see instant results, though, PDCA may not be for you. So if your organisation is dealing with an urgent process-oriented issue or you need fast turnarounds in performance and results, PDCA may not be the right fit. The cycle’s strength is in its ability to continually identify problems, then refine and find optimal methods. It’s less likely to completely transform performance metrics, for example, after a singular iteration.

Its simplicity belies PDCA’s strength: It requires rigour and mastery in order to truly benefit from it. But by adopting it – and sticking with it – you have a measurable way to create change in the way you or your team work. Successfully employing it at an organisation can help move all your colleagues toward a mindset of problem-solving and critical thinking. What’s better than that?