Having more control over their working hours actually makes people more productive, not less. “The big fear—that if you allow people autonomy over their time, productivity will fall—has proven to be groundless,” says Annie Auerbach.

The challenge then for individuals working remotely is to use more flexible schedules to their advantage: crafting boundaries, working when they’re most efficient, and not falling into the trap of never turning off. As Auerbach explains, “The last thing you want to do is to trade ‘place’ presenteeism with ‘digital’ presenteeism—to swap the 9-to-5 with the 24/7—because then we will just be importing the bad habits of the workplace into a new, flexible space and pretending that it’s true flex.”

Nicolas Leschke, CEO of Berlin-based startup ECF Farmsystems, says he’s learned how to create personal boundaries with the help of a few tricks, like turning off his phone at night and not making his work email too accessible on his phone’s home screen. “It’s very difficult to get it out of your head,” he adds. “But currently I think I’m doing pretty good in that sense. And I guess I had to learn it over time.”

Workplaces also have it in their interest to keep their employees from burning out. “People’s well-being—their mental and their physical well-being—is just absolutely critical to their performance,” says Kate Lister. “You didn’t hear things like ‘flexibility’ and ‘work–life balance’ and ‘mental health’ in the C-suite much before this, but we’re definitely hearing it now.”

As Annie Auerbach explains, flexible schedules benefit a wide range of workers—not only parents but also those caring for aging relatives, those with interests they want to pursue, and those who simply need more personal time. “It’s a new way of seeing things: rather than seeing flexibility as something that you have to grudgingly accept, you see flexibility as the way of the future, the way to attract the best possible talent, and the way for your workforce to feel fulfilled and balanced.”

Cook says she’s observed a newfound optimism about the power of technology to support people’s work rather than be a scary force in the background that threatens to take our jobs through mass automation. Instead, “It’s taking away some of the stresses of commuting. It’s giving us more time back with our family.”

“The COVID-19 pandemic has been a huge catalyst for digital transformation, as many businesses are forced to bring so much of their paperwork online,” says Whit Bouck, COO at e-signature company HelloSign (a Dropbox company), which allows distributed teams to sign official paperwork without needing to be in the same room. This can include everything from employee onboarding documents to contracts with suppliers. “Businesses need a way to continue making these important agreements online, and we make it easy and safe to do so,” says Bouck.

"I think the tools have a way to go as far as using technology tools to reinforce culture. I think we’re not quite there yet

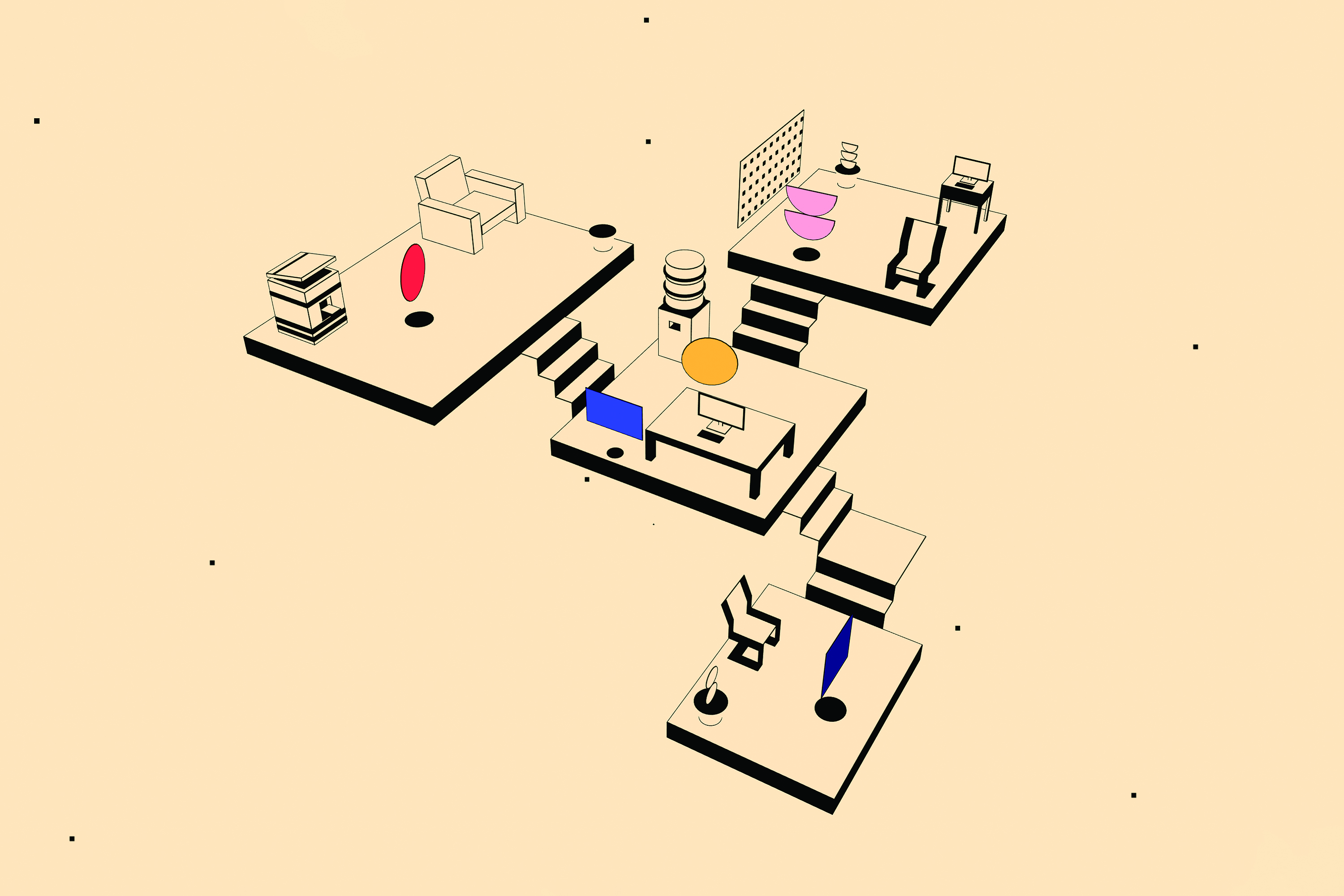

As teams adopt more and more types of digital tools—for adding an electronic signature, whiteboarding, project management, chat, and other collaborative activities—workers need to be able to easily navigate among them. Tools are starting to offer better integration so they can work in concert rather than compete for your attention. Case in point: In 2019, Dropbox launched Dropbox Spaces, intended as not only storage but also an important hub for collaboration and integration with other tools such as Slack, Zoom, and Trello. “We are becoming more platform- and workflow-oriented. Dropbox Spaces allows teams to bring together multiple files from different locations into a central place, enabling thoughtful collaboration. It’s really an evolution of what first made Dropbox a success,” explains Alastair Simpson.

Ultimately, digital work tools will need to do more for distributed teams than support productivity; they’ll need to support the emotional and creative needs of a community when its members are not in close proximity. “You do lose the novelty that comes from working around other people, the creativity you get from an impromptu coffee break, or inspiration from peeking at someone’s computer screen,” says Fred Wordie at Berlin-based creative agency Kids, who created I Miss The Office during pandemic lockdown to mimic the sounds of an office. He realizes the sounds themselves aren’t actually compelling, but rather the people producing them are. “That’s why many people find the site comforting.”

Creating digital alternatives for these accidental, informal moments among coworkers will be no small feat. “I think the tools have a way to go, as far as using them to reinforce culture. I think we’re not quite there yet,” says Kate Lister.

Many distributed workforces currently rely on team video calls, posts, and chat threads to build culture. Eventually, new features and tools will emerge to better support diverse and serendipitous encounters across an organization.

In some respects, connecting remotely also minimizes bias among everyday colleagues. Kate Lister notes that communicating virtually can reduce hierarchy, giving introverts and others a more equitable voice. “It really levels the playing field; everybody has the opportunity to have a say.”

As Annie Auerbach explains, the trope of being able to bond better in an office environment doesn’t express the full story. “There’s the fear that, working from home, we’re now isolated and not feeling a part of something. My big watch-out here is that we felt like that [wearing] headphones while not talking in the office. It’s not an issue of remote working—it’s an issue of remote connections.” Building trust among team members may ultimately depend less on specific tools or platforms and more on practices that are authentically human. Periodic social gatherings, or activities where team members get to know each other in deeper ways, can help.

Kate Lister adds, “It turns out from the research that we don’t need a lot of face time to maintain trust bonds. And, in fact, most of the virtual companies will get together maybe once or twice a year and often do nothing but socialize. Those infrequent get-togethers seem to be all they need to keep the level of trust high.”

Melanie Cook says her team created a virtual practice of two daily meetings during pandemic lockdown. The morning meeting is tactical, and the afternoon meeting is informal, replacing what might have previously been a casual corridor encounter. “Our afternoon chat is often sort of random. It’s just a sanity check.”

Expensive cities where workers have flocked for jobs might experience some relief, as people leave for suburban or rural properties that have space for a home office and access to nature. And some communities might even be able to revitalize their economies. “There are places across the country and across the world that are actively recruiting remote workers and giving them training; training locals to be good remote-work candidates; and, in some cases, even giving them a relocation stipend to move there,” says Kate Lister. “They’re desperate to add new types of jobs to their economies.”

Cities filled with flexible workers will organize themselves in new ways, rethinking the traditional commute between the residential and commercial zones of a city. C40 Cities, a global network of cities working to address climate change, depicts a world in which everything you need is accessible within 15 minutes of travel. Mixed-use city development—where home, work, retail, and entertainment happen in the same area—may even prove beneficial to work itself, as Goy has found in her architectural practice. “I discover new things when I go into the surrounding environment, to see, to touch, to feel, to experience, and to communicate with the community. I think to be a better designer is to get in touch with what is in the locale around me,” she says.

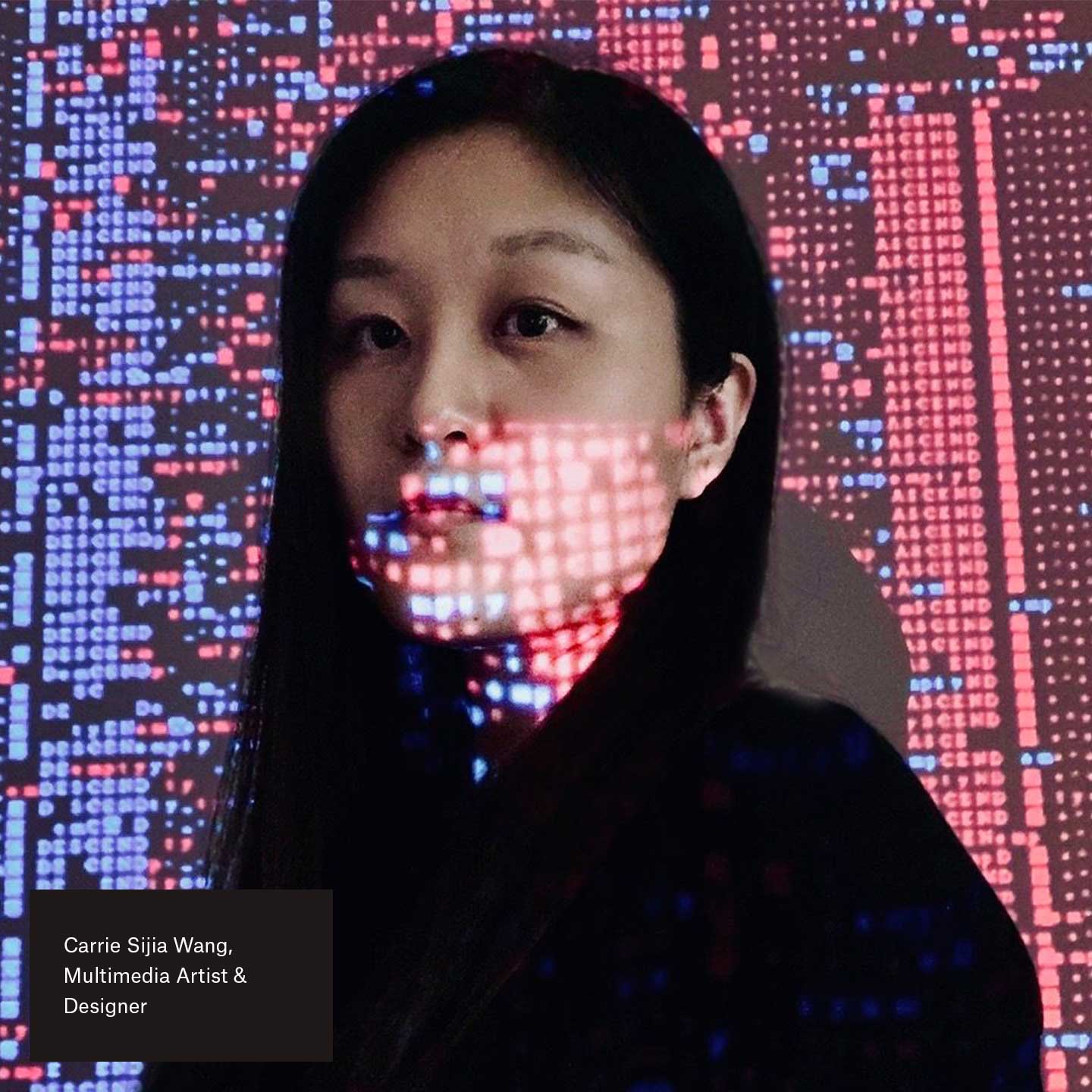

As some jobs disappear, new roles will certainly be created. According to a Dell Technologies report, the Institute for the Future predicts that 85% of the jobs that will exist in 2030 haven’t even been invented yet. People will become less essential for repetitive tasks and more essential for uniquely “human” skills such as critical thinking and collaboration. Melanie Cook predicts a “global upskilling emergency” in which people will need to be trained for these jobs of the future.

Auerbach adds, “We need actually to be educating ourselves throughout our lives. Education can’t be front-loaded because technology is changing, and skills are evolving, and we need to keep on scaling up, learning and relearning as we progress through our lives.” Accelerated training opportunities are already popping up to respond to adapting career needs, such as Google Career Certificates, are already popping up to meet this need.

Adapting to these changing circumstances means that many careers can no longer continue on autopilot. People may need to take a more proactive stance, exploring and shifting to find their stride. Auerbach says to expect “a more meandering path, where they might want to move horizontally or diagonally into different fields. They might want to stop and travel. They might want to stop and learn before they go back into the workplace. And so all of these visions are much more blended … as we move through our lives.”

Even in Japan, where companies traditionally have had a policy of lifetime employment, people are starting to think more flexibly about their careers. Tokyo-based En Factory provides a service that helps companies support their employees in getting and maintaining side jobs within the company and beyond. “Side jobs are becoming acceptable nowadays because their employees can gain new experience and new skills,” says Masaki Shimizu, chief business officer at En Factory. He sees side jobs as a win-win situation for both companies and their workers. Companies get to leverage the new skills that their employees develop, and workers expand their career prospects. Shimizu says most of En Factory’s own employees have side jobs, from building websites to providing clothing for dogs. He has four jobs, one of which involves running a hedgehog cafe. He said his approach to work was seen as very unusual when he started his side jobs in 2012—he was even featured in news stories—but now there are enough people doing it that he shares tips and best practices with them.

Freelancing and entrepreneurship will continue to be riskier and less stable than traditional full-time roles, so these workers will need better social safety nets. One example is Alia, a portable benefits platform for domestic workers like nannies, house cleaners, and caregivers. Several employers or clients can contribute to a worker’s Alia benefits, which may include paid sick days and access to insurance products like life insurance. “There are so many people working more than 40 hours a week [who] don’t have any kind of scaffolding or protection around them because those 40 hours may be spread over 40 worksites instead of a single employer,” says Palak Shah, founding director of NDWA Labs, the organization that created Alia. “Alia is the canary in the coal mine for the future of work; we knew that if we could solve these problems for domestic workers, we could solve them for every worker.”

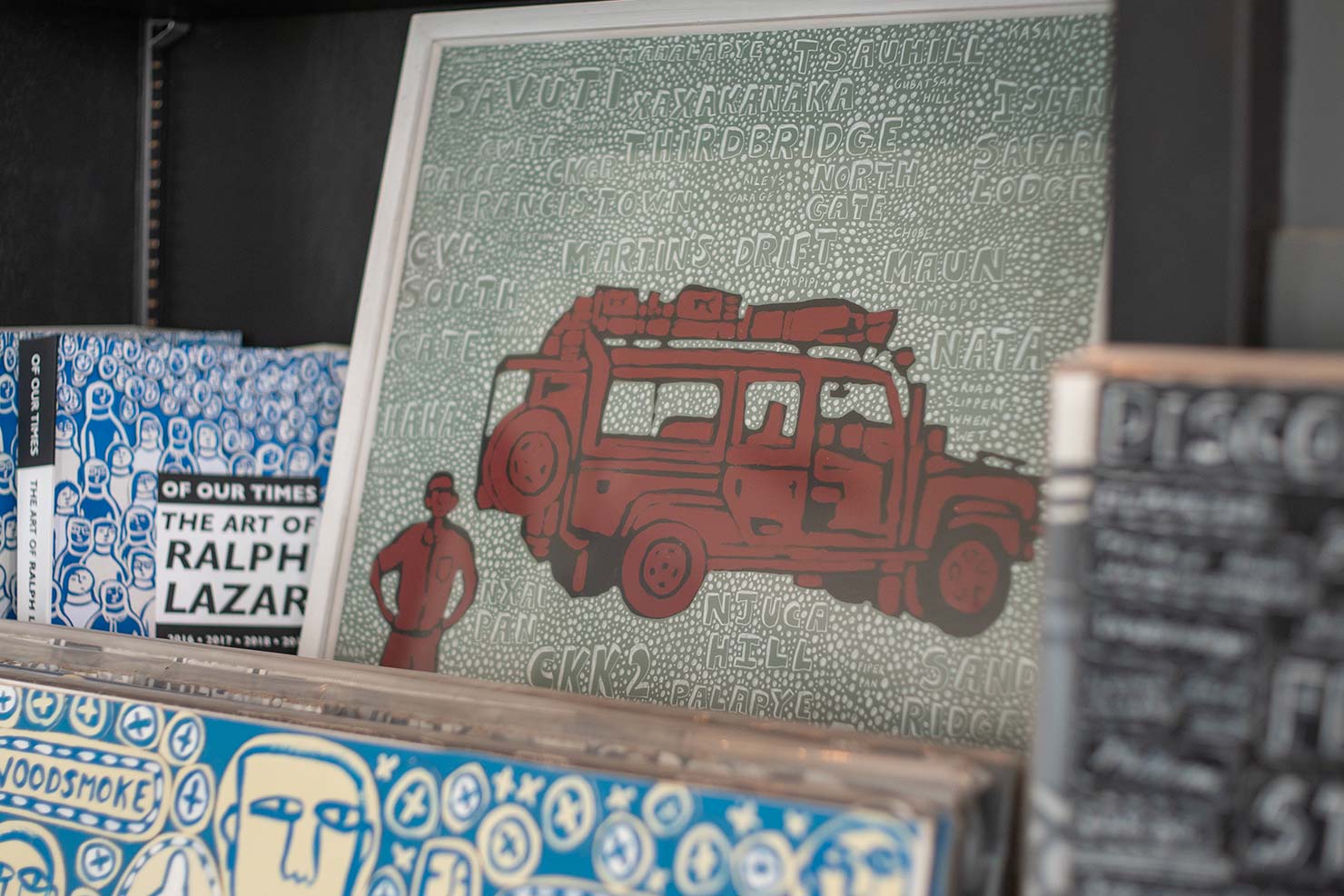

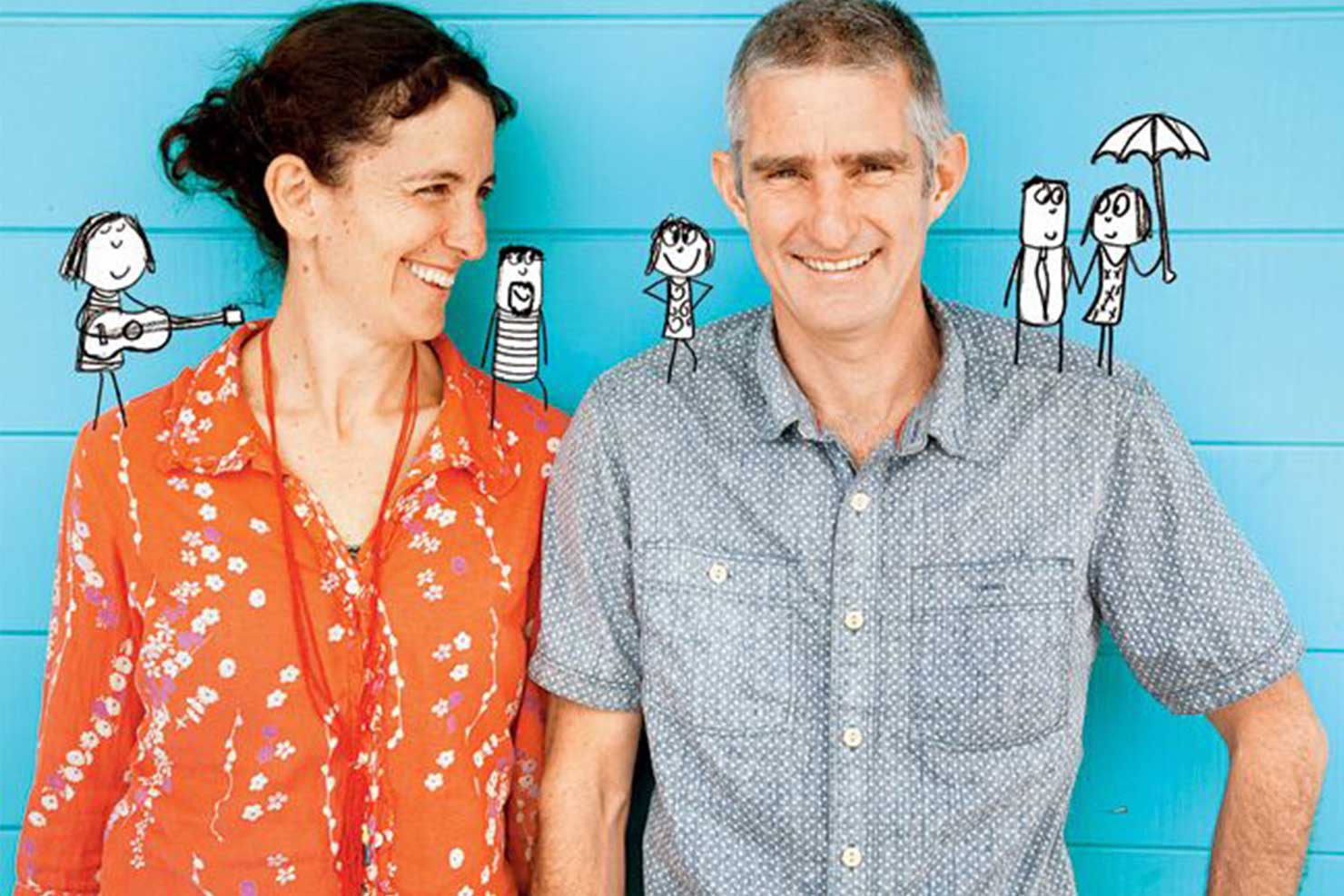

Artist couple Lisa Swerling and Ralph Lazar embody the meandering path that may lie ahead for many: “What we always find interesting about our story, because we’ve got to a really amazing place, is it is checkered with failures,” says Swerling. “And it’s hilarious, and it’s inspiring, because first of all, we are blessed with a kind of innate optimism. And you couldn’t really do what we do without being optimists, because you wouldn’t keep going. ... You have to keep reinventing your work.”

Ultimately, people will continue to seek purpose and fulfillment through work, even as their journeys take more twists and turns. Nicolas Leschke at ECF Farmsystems describes this sense of fulfillment for his current role: “You’re within the city boundaries; you have a green job, which is very satisfying; you work with something that is natural. And I think that all gives you good karma.”

Zhenru Goy at Goy Architects says their flexible work model allows them to slow down and evolve gradually, to work as purposefully as possible. “We are still experimenting and figuring out what we should do for architecture, so there is a constant contemplation of what and how we should contribute that is of benefit to the community and environment. … We can take the time to think, but we are also nimble in our practice, and we can make an impact with our projects.”

Melanie Cook suggests approaching your entire career with “slow thinking” as opposed to panicked, fight-or-flight responses to what’s happening in the world. She recommends “giving yourself the time to really plan your career and plan some experiments … in order to find the most successful path for you.”

Kate Lister hopes workplaces will find better ways to identify and leverage people’s skills, interests, and strengths. “That’s when we’re going to get the peak performance from people,” she says.

Ultimately, flexible approaches to the future of work will enable us to confront what lies ahead, do good work, and adjust to whatever arises. Our flexible futures will demand resolve in the face of adversity. As Melanie Cook says, “The optimistic point of view is that humans have an incredible resilience. They can adapt, they can adapt, they can adapt.”

Our flexible futures will also empower us to focus proactively on what matters most to us. Changing work circumstances will present an opportunity to find better ways to balance our priorities—from passions to people to the professional pursuits we find most meaningful and worthwhile. We should ensure that every aspect of a person will find a way to thrive, and that the ultimate outcome is as much about life as it is about work. Because, as Annie Auerbach says, “There’s always a very human story behind why people want to work flexibly.”