Education is changing

As the world continues its shutdown, people’s perspectives of what is and isn’t essential are evolving. Friday night dinner out? Sorely missed, but we’ll live. Getting a professional haircut? Calamities have ensued—but it’ll grow back. The loss of jobs and economic impact? Disastrous. And there will be permanent consequences for many people. But—in aggregate—this isn’t the first global recession, it won’t be the last, and it will get better in the long run.

Unlike dealing with a bad haircut or even lost income, there’s no way to re-create the formative years of a young person’s education. You’re only in seventh grade once, learning the difference between an obsidian and sedimentary rock—if you’re super lucky, this came with a field trip. Freshman year biology lab, with all its bunsen burner-related mishaps, happens one time.

COVID-19 has changed the very nature of education in 2020, closing down schools for over a billion children, affecting 90% of the world’s student population. Parents have responded with home-schooling efforts and K-12 teachers have attempted to keep the curriculum going to varying degrees of efficacy. One of my friends, Laura, a second grade teacher, tells me how hard it is to keep kids engaged on video. “They just want to show me their toys,” she says.

The loss of a school semester or an entire grade can feel even worse than a down financial quarter for a business. And with possible recurrences of the virus unknown, it’s unclear how long schools will need to remain closed.

For now, those lucky enough to have the resources rely on technology. Even then, Christina Paxson, President of Brown University, tells the New York Times that there’s no full-fledged replacement for the “fierce intellectual debates that just aren’t the same on Zoom, the research opportunities in university laboratories and libraries and the personal interactions among students with different perspectives and life experiences.” But we are finding that schools, educators, and students are especially reliant on technology right now as a complement to what they do. And that may have lasting impacts well beyond 2020.

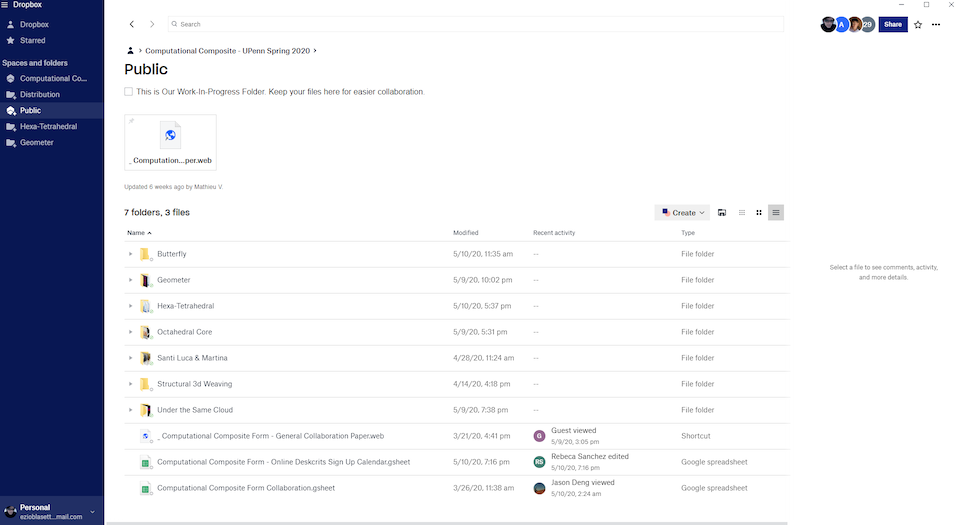

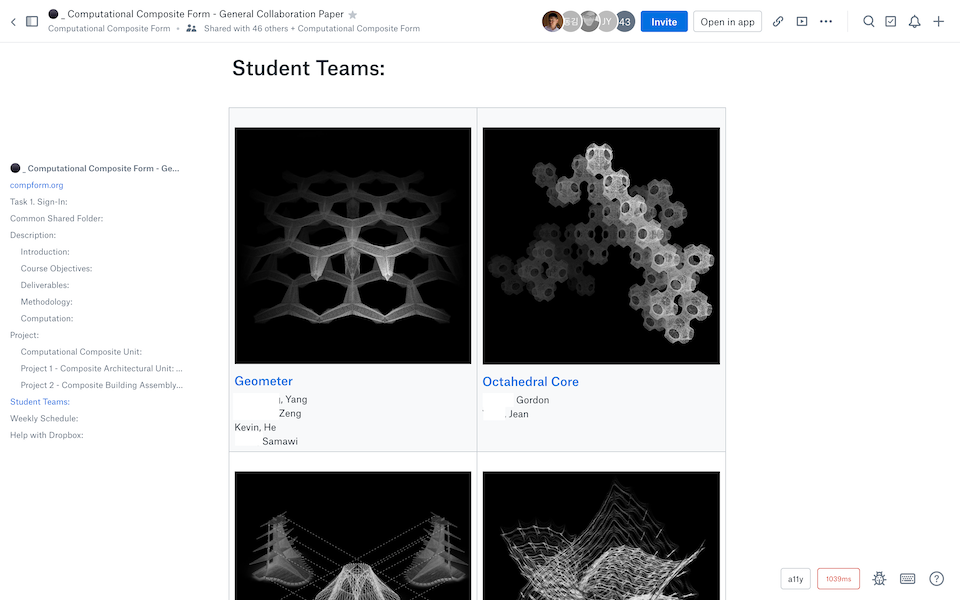

Ezio Blasetti is a Lecturer in the Graduate architecture program at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design, currently teaching the seminar Computational Composite Form. In layperson’s terms, his architecture students are programming robots to construct buildings. The class was originally building an installation for the Venice Biennale, one of the highest-profile architecture events in the world, but that event is now in question as Italy recovers. Either way, learning hasn’t stopped: the class is an exploration both into the arts and highly technical disciplines of engineering and mathematics.

Since Penn closed its campus on March 11, including the robotics lab from which students tested and iterated on their fabrications, Blasetti’s class has moved virtually to Dropbox and Zoom. Class agendas, assignments, and sharing of assets and ideas takes place in Dropbox Paper.

“Dropbox was absolutely critical for me to get my class back together,” Blasetti says. “The potential is beyond just putting the information together in one place. We use it as a collector of many different ideas that work or maybe don’t work over a project cycle, and the jumping off point for discussion.”

“Dropbox Paper imitates the advantages of a physical workspace,” adds Penn student Kevin He. “The way you can group share, have edit history; I start to see where technology provides an advantage. We can augment our workflows especially since we’re frequently working with large files that can’t really be emailed back and forth. So we’re finding it really intuitive and useful.”

While everyone is in a different place, the class uses Paper as a virtual meeting place to come together—even if that means they “see” their professor more than usual. “The immediacy feels like the most dramatic change,” says student James Billingsley. “At any point, the instructor could potentially drop in and begin engaging with the work.”

Billingsley continues: “It's one of these modes of relation we don't have norms for yet. Sometimes it's surprising, for instance, to be talking about work casually with a collaborating student to then have a professor drop right in. It’s simultaneously a more and less intimate setting than our normal class, which is an odd, but cool feeling when we’re all apart.”

“With the right infrastructure, there’s so much potential to scale and democratize education.”

Ezio BlasettiLecturer, University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of DesignFor all the pros and cons of distributed education right now, Blasetti sees potential for its expansion. “The conversation about privilege is an important one, and yes, many people around the world don’t have access to computers or the internet. But instead of just saying that that’s a negative of technology, I think we should be making it a priority to increase the spread of tech in more cost-efficient ways.”

“With the right infrastructure, there’s so much potential to scale and democratize education,” Blasetti says. “There’s experiments going on now where people are self-organizing to host classes no matter where people are from, with translations into 40 different languages. Professors don’t even know how many people are dialing in. When you start to think about people in war zones participating in online classes, you can imagine a completely different type of life. Educators have actually been talking about this for years, but now that we’re dealing with this pandemic, the concept has become a bit more real.”

Christina Han, M.D. is frustrated by the misinformation that her patients are receiving. As a physician caring for high-risk pregnancies and an Associate Professor at UCLA School of Medicine, she can’t just sit on the sidelines as confusion and falsehoods about the nature of COVID-19 spread around the internet.

“Right now we need to let the science lead us, and I thought it was important to share the information widely, efficiently, and in an organized fashion.”

Christina Han, M.D.Associate Professor, UCLA School of MedicineHan’s specialty is maternal-fetal medicine, and recently posted a public Dropbox folder with publications, guidelines, and presentations on pregnancy during the pandemic. “I’ve been using Dropbox personally and professionally for a very long time,” she says. “It’s just the easiest and most efficient way to house living folders and documents that my colleagues, trainees and patients can access in real time. I never thought I’d share a Dropbox folder as publicly as I did, but it was an easy way for me to get detailed information out to the masses.”

“As a researcher, clinician and public health advocate, I felt an obligation to share scientific knowledge during a time when people are so concerned with their own health and that of those around them,” Han says. “Right now we need to let the science lead us, and I thought it was important to share the information widely, efficiently, and in an organized fashion.”

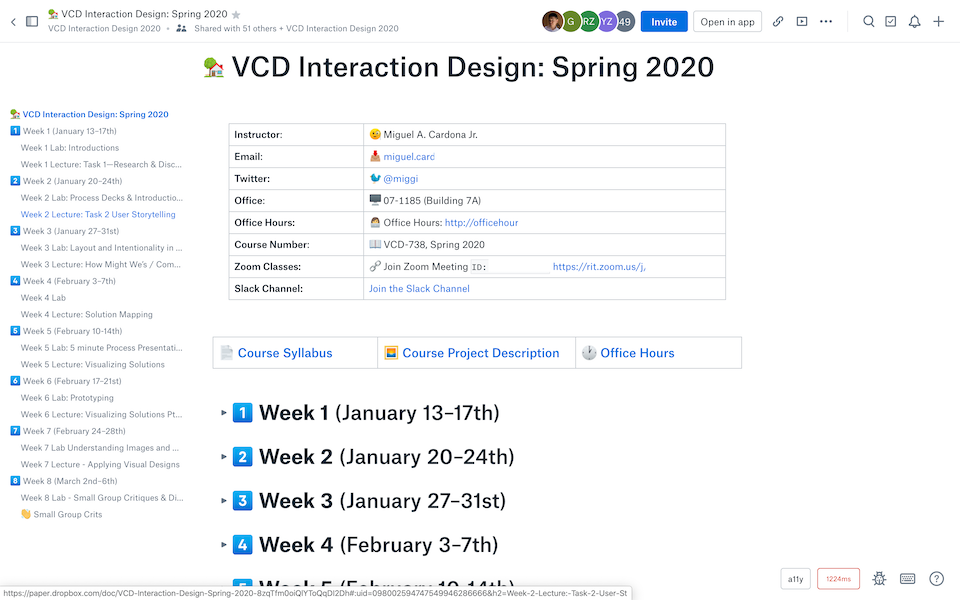

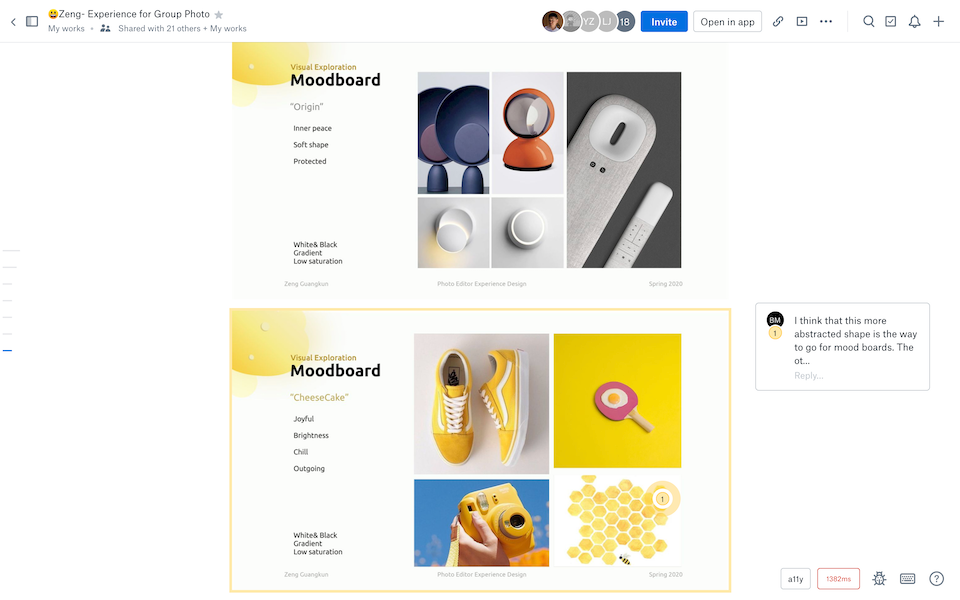

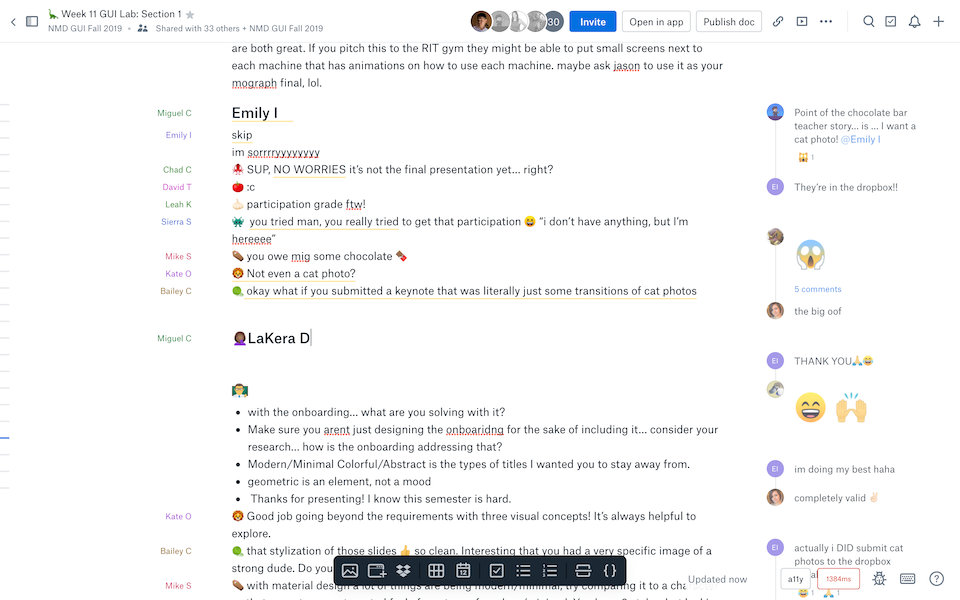

RIT’s School of Design is one of the nation’s best, and designers by trade tend to be forward-looking. So perhaps it’s no surprise that for RIT Assistant Professor Miguel Cardona—a Dropbox, Slack, Figma, and Zoom evangelist for years—the transition to distributed education has been relatively seamless.

“Our department has long felt that it’s important to be agile,” Cardona says. “No one could’ve predicted this situation, but thankfully we already have the muscle memory of discussing, sharing, and collaborating online.”

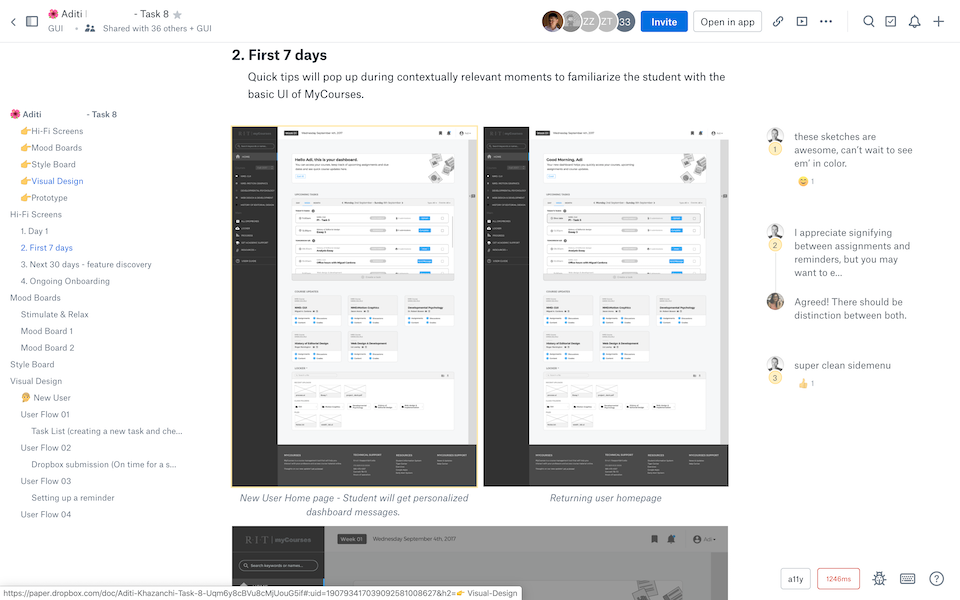

Cardona, a Dropbox Paper user since 2016, organizes all of his class agendas, attendance, student to-do’s, Figma and Dropbox file links, project feedback, and even his students’ favorite emojis in Paper. “It’s great to have the design file in the same place as feedback, so students can go point by point with the right context.”

He’s found it especially helpful for larger classes, even before the pandemic: “In larger lectures, students don’t always have the opportunity to give verbal feedback, and they also tend to be more quiet in larger settings. With Paper they can share ideas in real time, as a student is presenting.”

Dropbox integrations with tools have also helped in the transition. “It’s been particularly invaluable during COVID-19 to have backups of Zoom lectures. Without skipping a beat, I’ve been able to switch from in-person to online. All the students already knew where to go and felt prepared and confident in what they were doing,” says Cardona.

“We’re embracing these formats to make the course concept more accessible during a time when we’re re-defining what a ‘classroom’ really means.”

Miguel CardonaRIT, Assistant ProfessorCardona also sees benefits to distributed education beyond adhering to social distancing. “One of the reasons I use Dropbox Paper in my classroom is to benefit deaf and hard-of-hearing students. If I'm doing a demo, it's much better for me to copy screenshots and throw those into a Paper doc with a comment. While we’re working live, they can follow along and post questions. We’re embracing these formats to make the course concept more accessible during a time when we’re re-defining what a ‘classroom’ really means.”

“I also have international students, so creating this distributed environment has been beneficial to them, while they deal with the uncertainty and implications of traveling back to campus,” Cardona says. “No one wants this pandemic to go on any longer. But I do think that necessity can breed innovation, and many educators have been searching for that for a while.”

Technology is the key to the future of education

Distributed education is imperfect. Students, faculty, and parents around the world surely can’t wait for school to resume, especially for young children. None of the above educators would likely recommend distributed education as a full-time replacement for in-person learning, for those able to receive it. (Not that it would even be possible—despite technology’s aim to scale, only 60% of the world’s population is online.)

But one thing these three stories have in common is that underlying their enthusiasm for technology is a desire to make knowledge more accessible. In the chaos of this pandemic, educators are being forced into new models, and, consciously or not, thinking about ways to serve broader audiences—the diversity of their current students becomes accentuated when they’re not in the same physical place.

Today, distributed education is doing its best impression of in-person learning. That’s a tall enough order as it is. But it’s also being tested as a long-term model for bringing education to more people, regardless of their location, needs, or resources. These innovations could leave an indelible mark for the benefit of young people who—even after this pandemic is over—face persistent challenges to getting a quality education.